‘The Politics of Evidence’ in my Daily Working Life

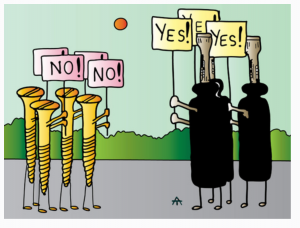

One problem we face in the evidence debates is the use of single examples to assert a generalization or uphold certain positions. This led us to organize the crowdsourcing of experiences as input to the Politics of Evidence conference. With 150 stories shared online and 70+ to be debated at the conference, prescription more grounded discussion becomes possible to generate nuanced insights about ‘the politics of evidence’ and nudge us beyond simplistic yes/no positions.

One problem we face in the evidence debates is the use of single examples to assert a generalization or uphold certain positions. This led us to organize the crowdsourcing of experiences as input to the Politics of Evidence conference. With 150 stories shared online and 70+ to be debated at the conference, prescription more grounded discussion becomes possible to generate nuanced insights about ‘the politics of evidence’ and nudge us beyond simplistic yes/no positions.

I’ve been taking a fresh look at my own work with a ‘politics’ lens and see it in small and larger forms in many nooks and crannies. Below are some recent work situations from the past five months in which I am directly involved. They illustrate how I see the ‘the politics of evidence’ playing out in designs and decisions around what Brendan has described as the (small and big) E of evidence– the results and target oriented issues, cialis and those that relate to evidence of what works.

- Method before question. Working with an aid agency to think through an impact evaluation, the words ‘really rigorous’ and ‘scientific’ are used in relation to assessing the impact of new service delivery model. An RCT design is scoped that assumes one can identify comparable clusters. Yet the service delivery being evaluated is highly diverse in implementation, within a very dynamic sector with multiple parallel reforms. The agency involved recognises the need to step back from assuming a particular method is the only rigorous option and to first ask ‘what do we want to know’ and then figure out what’s appropriate. Can we collectively generate rigorous and scientific alternatives that satisfy accountability needs and also fuel the critical learning they want?

- Sampling. One organization is testing out a participatory impact assessment approach (for large E questions). A good sampling approach is essential, with the assumption being that a counterfactual comparison of a representative sample is required. But other sampling options exist that allow for sufficient scale to generalize, without diluting the in-depth analysis and participatory reflection and action that make possible rigorous findings. We need to meet the needs of statistical rigour, as well as utility rigour. But if we can’t manage this, which version of rigour will be the non-negotiable? And will we be allowed to ‘get away’ with contribution claims or must we comply with narrower attribution norms?

- Grounded theory of change versus impossible goals. In Africa, an NGO has just been given a grant to work with social media to strengthening democracy. Project staff elaborated a more detailed version of their theory of change for which the grant had been given. They located their own efforts within a sea of diverse kinds of change that are needed for democracy to be possible. Doing this, however, left them feeling rather morose as it made it clear that the grant is asking them to achieve the impossible. The funding agency and the implementing NGO both know that the contractually agreed goals are totally unrealistic yet the funder will not allow these to be changed – the ‘small e’ of evidence of results and targets. This insistence is making it impossible to really understand how social media work contributes to political change (large E). And staff already know they will fail to deliver.

- Alternatives for organizational accountability. In Vanuatu, the Pacific Institute for Public Policy has the mandate to trigger national conversations that serve democracy. Tracking this via a logframe would contribute little – the change process is neither predictable nor linear, which is recognized by funders and implementers. So they have agreed to an approach that tracks anecdotes of shifts and compares these with the evolving understand of desired behavioural changes of key political players. A case where the politics of evidence was not a battleground and commonsense has so far prevailed.

- And then there is the daily politics of evidence around who misplaced the car keys but that is another story altogether!

In wading through the politics, I find it helps to be clear about the underlying worldviews of those involved. I reassure myself that policy is never evidence-based, but hopefully can be evidence informed – and that we all value evidence. None of this is particularly shocking or unique. Yet tensions and tussles around evidence and its politics persist. This and much more will be debated at the Politics of Evidence conference at the end of April in Brighton, the UK. Stay tuned…

Comments are closed.