Reclaiming Value for Money

RECLAIMING VALUE FOR MONEY: THE BIG PUSH FORWARD?

During the Big Pushback meeting last September we discussed growing pressure to demonstrate aid provides ‘value for money’ (VfM). We agreed the need to find ways to communicate aid is well spent, ask but were less sure how to do it. Some were keen to resist reductionist, ask results-based approaches that reinforce perceptions of aid being about service delivery, rather than transforming power relations for social justice. Defining the ‘unique selling point’ of rights-based, relationship approaches that may offer greater prospects for sustainability than service delivery was proposed as one way forward. Outright rejection of calls to measure the outcomes of aid used to uphold moral principles, such as preventing human rights abuses, was another.

A lot has happened since, and this launch of the VfM action research aims to begin the process of developing shared understandings of how the VfM agenda is shaping up in different locations. What is being demanded? By who? Where? How are practitioners responding? Are we finding ways to reclaim and define value for money’ in terms consistent with a social justice agenda? To get the ball rolling here is my very partial understanding of what is going on in the UK . I warmly invite others to contribute analyses of what is happening elsewhere.

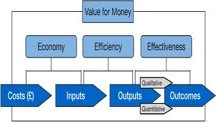

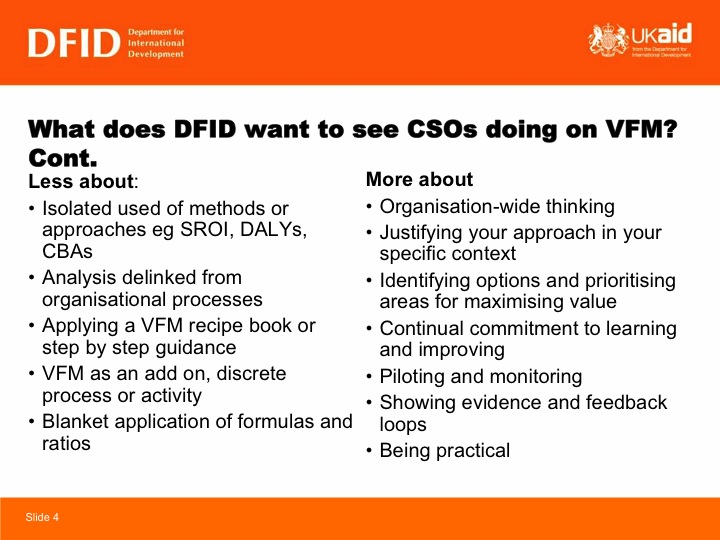

DFID aid reviews, evaluation TORs and presentations at VFM events seem to send a consistent message: VfM includes elements of economy, efficiency and effectiveness. However, at meetings I’ve attended, DFID staff emphasise we should be thinking of VfM as a systematic approach to increase impact tailored to each organisation particular, rather than a call to apply blanket formulas.

What does this mean in practice? Well, establishing systems to reduce financial risk and enable monitoring and evaluation is essential. And from what I have seen, DFID funding relationships – at least with CSOs and private sector actors – appear to revolve around ‘business cases’. Applicants are expected to demonstrate proposed interventions have been selected through systematic scoring procedures that weigh up the relative pros and cons of various options. My review of one case gives the impression unit costs per output or outcome are the most popular monetised metric used to support this ex ante decision-making.

VfM metrics are to be monitored and reported during programme interventions. So obviously those wanting to access funds will need to be able to measure and quantify outputs and outcomes. In the case of simple service delivery projects this may be relatively straightforward. But calculating cost per outcomes in more complicated and complex project contexts that involve capacity building and/or relationships between multiple stakeholders is quite another matter.

I recently had to conceptualise the VFM approach for an evaluation of a complicated DFID funded civil society governance programme involving partners in more that 80 countries. Given it had influenced policy and government behaviour it was easy to use various cost data to make an intuitive argument that DFID was getting a good VFM. But it raised common questions. How should results and VfM be conceptualised in a short-term donor funded project that is only part of a longer-term organisational strategy and theory of change? How should the essential contributions of a vast range of actors, many of whom were not supported by DFID’s funding be reflected? Did reliance on considerable volunteerism represent an economy and if so, is it likely to be sustainable?

At the time I viewed my approach, which drew attention to these issues while also demonstrating how vital individuals and relationships had been to success, a mini pushback. But was it really? Now I’m not so sure. Appropriating market-based concepts like ‘efficiency’ and ‘results’ for the VfM analysis was hardly progressive. Should we be using such terms to describe interventions concerned with challenging inequitable political economies and the power relations that sustain them? Does such language and thinking reduce their transformational possibilities? Should we instead be trying to influence conceptualisations of VfM so they are more consistent with principles of solidarity and social justice, e.g. by advocating:

- Transaction costs be redefined in terms that reflect the critical roles that individuals and relationships play in social change;

- Impacts of aid actors be defined and measured by those they aim to enable;

- Changes in power relations be made a fundamental measure of success;

- VfM considerations include moral as well as market based criteria when it comes to considering the relative VfM of human resource costs.

Responses to questions above are likely to be influenced by personal politics, interests, theories of change, and positions in the aid architecture. Some organisations and individuals within them enjoy greater opportunity to campaign for more ideological ideas than others. So while it is crucial to reflect on how to take forward more normative aspects of the ‘reclaiming VfM for social justice’ agenda, we also need to think about practical ways to support those tasked with responding to immediate challenges. A great deal is already happening. Save the Children have commissioned students from the London School of Economics to explore how NGOs in UK are interpreting and responding to the VfM agenda. BOND is working with UK NGOs to develop a common position. I look forward to learning more about these and the initiatives of others actively involved in responding to the VfM conundrum.

Cathy Shutt

Comments are closed.