Power: a useful lens for thinking more politically?

During the convenors’ reflection on the recent Politics of Evidence conference we wondered whether more nuanced power analysis might help us break out of unhelpful linear aid chain mentalities related to results and evidence. The case studies presented at the conference suggest that if we are to make the results and evidence agenda more supportive of transformational social change we need to move away from the idea that the politics of evidence is all about visible power. Images of monolithic all-powerful donors placing unreasonable evidence and results demands on well-intentioned, store powerless recipients are not very helpful. Many of the experiences shared suggest we need to get more adept at identifying how hidden and invisible power influence the use of results and evidence artefacts in different contexts by individuals from different cultural backgrounds and who possess varying capacity and confidence. Such an understanding might enable us to develop more politically savvy strategies and tactics to harness useful aspects of the results and evidence agenda whilst mitigating the risks of it being used in ways that could contradict transformational development aims.

- Visible power: formal decision-making mechanisms, rx e.g. donors insisting on the use of certain results artefacts, such as logical frameworks and reporting formats

- Hidden power: a mobilisation of bias, e.g. not inviting small NGOs to attend meetings about results frameworks

- Invisible power: social conditioning through cultural traditions, ideology, etc that shapes the psychological and ideological boundaries of what seems possible, e.g. practitioners being conditioned to accept the results agenda and the use of certain artefacts, e.g. indicators as the norm; recipients feeling they can’t challenge donor decisions; INGO programme managers feeling they can’t challenge normative organisational norms and beliefs relating to the production and use of results and evidence.

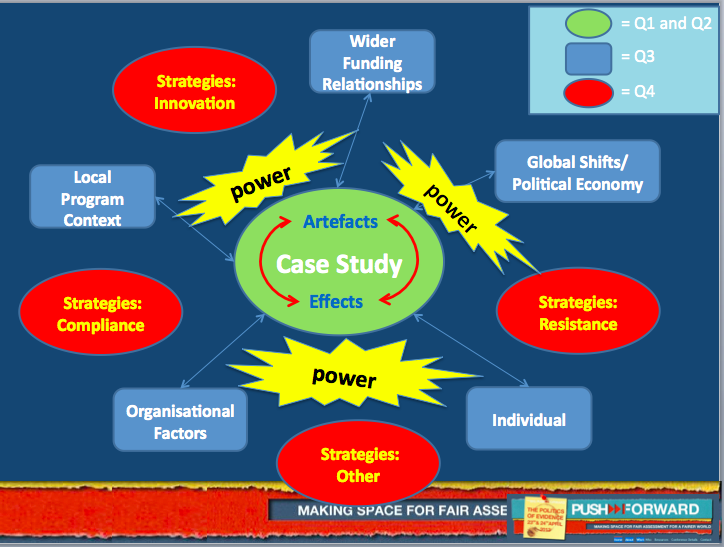

Firstly, a brief recap for those who weren’t there. Case studies presented on the first day indicated that there is nothing inherently good or bad about evidence and results tools. We explored both positive and negative effects of ‘artefacts’/tools such as logical frameworks, cost benefit analysis, theories of change etc (green in diagram below). Some examples suggest that theories of change are being applied to evaluative practice in ways that empower practitioners to usefully interrogate their assumptions about how social change happens. However, a case presented by an organisation working on rights for women with disabilities illustrated how such tools can be used in ways that, perhaps partly as a result of hidden power –their lack of involvement in discussions about results frameworks, undermine a sense of ownership.

We also heard stories of how efforts to demonstrate effectiveness through impact evaluations can fall short when it comes to encouraging organisational learning for social change. I wish we had kept a count of the examples of expensive evaluative processes that failed to meet participants’ expectations that they would produce incontrovertible evidence to inform decision-making. They raised questions about whether expectations that they can are an operation of invisible power? Furthermore, discussions on the second day confirmed that even if it were possible to produce irrefutable evidence, it would be impossible to apply it objectively to learning and decision making given the complex politics at play in most development organisations.

Revelations about the role that senior managers of INGOs play in incentivising the reporting of ambiguous results – such as numbers reached by campaigns – exploded myths about institutional donors being the sole agents imposing artefacts in unhelpful ways. A nuanced power analysis can help us better understand the political factors and conditions that influence the use of results and evidence tools (blue in diagram above) e.g. senior management’s role in shaping organisational cultures and norms Such a power analysis might also inform assessments of which practices are benign and which potentially dangerous and thus what kind of strategies (in red above) are appropriate responses.

Several empowered practitioners I spoke to argue that responding/complying to demands for large number results e.g. number of people reached can be a strategy consistent with transformational agendas. They are of the opinion that it is easy for practitioners to satisfy political requirements and come up with what Brendan Whitty in his crowd sourcing report (page 16) refers to as ‘sausage numbers’. For them resistance – arguing about the meaningfulness of such figures is not a good use of energy they would rather devote to learning about how change happens. Yet some evidence collected through the crowd sourcing report suggests that enormous effort can go into generating such numbers at the expense of learning. Moreover, case studies, like the example of the INGOs above hinted that if practitioners are asked to measure effectiveness in terms of ‘numbers reached’, compliance could affect the ways they view the aims and success of their practice. I certainly saw evidence of local NGO frontline staff starting to see development success in terms of numbers of people reached by interventions during research in Cambodia. Several conference participants felt that these interpretations of results tools privilege upward accountability and need to be challenged. One group suggested that by articulating accountability to the citizens development organisations work for as a measurable result it would be possible to shift power relations and make a focus on results more supportive of transformational change.

Many strategies proposed by conference participants in the last session suggested greater awareness of how power influences the conditions (above) can in itself be empowering. Strategies shared demonstrated a heightened sense of personal agency, confidence and ‘power to’ resist inappropriate use of some artefacts or negotiate organisational politics to frame results in ways supportive of transformational development. Some conference participants that might have previously felt isolated identified ways to collaborate with kindred spirits in donor organisations, INGOs and practitioners working on the frontline. During our post conference musings we wondered what more we might learn from feminist and gender experts who have years of experience using power analysis to inform their efforts to mainstream gender issues both in programmes and in the ways their organisations are managed.

Comments are closed.

The diagram is not visible!