Theories of Change: Breaking out of the Results Agenda

A couple of weeks ago, pharmacy someone phoned me from a large INGO to explain that his organisation was under increasing pressure from its government donor to ‘do a ToC’ in its funding proposal. ToC had become an additional mandatory results-based management tool constraining the INGO’s partners from designing projects based on their own strategic decisions. This is a real shame because a dialogue about the change desired and a theory of how to achieve it can be useful provided we recognize that any explanation is partial, and contingent on context and needing to be regularly checked against reality, as experienced from diverse perspectives.

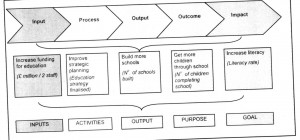

This is different from how my interlocutor’s donor organisation understands the utility of theories of change. Figure One is that donor’s ‘Logic Process of Developing a Theory of Change’. It reflects the linear cause-effect thinking of Figure Two from that donor’s guidance on log-frames. ‘Impact’ in the latter is ‘desired change’ in the former; ‘pathway of change’ includes both the ‘strategic results’ – more children through school – and the conditions necessary for achieving these. ‘Conditions’ are what used to be called ‘assumptions’ in the fourth column of log frames. A generation ago, this column could be used to recognize the dynamic social and political environment of aid projects, thus introducing uncertainty, requiring iterative process planning. Perhaps there were other routes to increasing literacy that became apparent during project implementation? Possibly, an unforeseen event has occurred which requires a quite different kind of response? Today the logframe is a rigid tool, demanding ever more precise and pre-determined ‘results’ with SMART indicators. In such circumstances, the ToC opens things up by again asking questions about assumptions and conditions – and this may explain its popularity. Unfortunately, however, the ToC becomes just another oppressive hoop to jump through in a managerial environment that has not changed and that still requires a rigid log frame.

Cathy James points out in a recent review of ToCs that many people use cause-effect thinking for accountability purposes: have you clearly formulated in advance the result you expect to achieve and why? She also suggests it can be a useful for project cycle management – certainly the case if we can avoid a blue print approach. Otherwise, such a tool hinders organisations in contexts when there may be different causal mechanisms at work from one location to the next and that need to be identified, discussed and debated among the stakeholders involved – challenging when power relations are unequal and some people’s values, experiences and beliefs about how change happens may be ignored (although their actions will influence outcomes). This is why I favour another approach to theories of change

This aims to surface and discuss people’s tacit theories about how change happens, to guide their broader strategic thinking rather than articulate a pre-determined pathway towards results. It is an approach to learning, reflection and analysis that accepts differences of opinion. It recognizes that:

- Choosing one theory over another is not a purely technical matter of which theory fits the context, rather, any model of societal change is political and value-laden.

- Power and position shape our ideas about change. Development organizations, the communities they work in and their partners may all have different theories of how history happens that influence strategies for action.

- Theories are always partial – there is not one theory of change that is universally applicable. In each and any context dialogue is the basis for choosing the possible different ways forward. There is a good case for organizations in an alliance to agree to use two or more different approaches on the basis of political contingency and the positionality of those involved. I am dubious about any organisation having a single ToC that applies in all and every circumstance. That is just performing for the RBM machine. It is not about usefully working with others for social transformation.

Comments are closed.

Hello. This is a verry intresting discussion. Although Im still a bit confused. Im studing Global studies at Jönköping University and writing right now a essay about Theory of Change. And Im not refering to ToC model but the approach that Rosalind are adovacting. Im verry thankful for more resorces in the issue.

Björn

Hi all – this is a very interesting discussion. At TechnoServe, we are engaged in our next 5 year strategic planning work. Over the past few years we have developed and rolled out across the organization a logframe approach to our project level planning that provides the basis for results based management at the project level. We are now looking to develop a robust theory of change that will provide the basis at organization level for setting goals and outcomes for the next plan, tracking against them etc. At the moment we are building that theory of change/goals framework in a similar format to the logframes we have at project level – using a similar linear logic methodology. There are challenges to doing that – some of which are a) to ensure that it is sufficiently flexible to allow for local responsive creativity in the countries in which we work (which may mean that assumptions in one context are interventions in another); b) that it facilitates strategic prioritization about what we will focus on – especially at activity and output levels, and c) that it allows for learning loops to amend the beliefs and hypotheses embedded within the theory of change. So my question for now is … does anyone have any examples or models of organizations that have developed their strategy in a way that links a theory of change to goals through some form of logic framework ?

Thanks

Simon

Hi Simon,

Its difficult to explain this without demonstrating it with an actual case in front of us, but the approach we have developed at Keystone creates a very clear framework of ‘outcome pathways’ using a ‘systemic logic’ rather than a linear one. Based on this framework, you can design a set of specific but often overlapping strategies (because each strategy can contribute to a number of the identified outcomes as well as its primary outcome) focused on achieving outcomes identified in the framework. If the outcomes are clear and the context not too complex, then simpler linear logframes are good for some specific strategies.

Tracking progress and measurement then involves setting performance goals in terms of outputs AND gathering evidence of the changes (including things like relationships, attitudes and other preconditions of success) that you want to see. Our latest work focuses on simple and regular feedback systems that turn constituent feedback into quantified performance management data using tools and questionnaires that derive from the theory of change.

Have a look at our website for ‘the really busy person’s guide’ to constituent voice (can’t attach anything to this reply). and feel free to get in touch if I can help at all.

Hi Laurie

Thanks for this. Yes, I agree ToC approaches do help people plan what they are doing. They are what I call ‘theories of action’ as distinct from ‘theories of how history happens’. In workshops I do with development organisations, I encourage participants to surface their implicit theories about how history happens so as to appreciate how these inform strategic choices and the kinds of activities they decide to undertake. It also hleps them appreciate that not only might they not all share a common view within the organisation but there can also be differences between them and their partners or their donors that if left unexplored can undermine shared purposes.

Rosalind

We are using DoView software to allow us to do simple flow charts of the logic from actions to outcomes to impacts, with related indicators, to try to get programmers to be more explicit about their ‘theory of change’ (I still think its quite a grand word, isn’t marxism a theory of change, …but anyway…)

The challenge – as always with tools in my experience- is that staff instantly jump on it in a reductionist way – thinking it replaces the fuller programme design process. ‘What about power’ ‘What about participation’ a recent email asked me.

None the less, it does seem to be helping. As much as I hate to accept it, majority of colleagues do want predetermined formats and instructions, and using a flow chart to express the linkages (or ‘theory of change’) is proving more useful than the narrative questions and tables we’ve tried before.

And thank you to DoView for giving us many extra copies of DoView donated so that we could trial this.

This is a great discussion.

I’d like to add two thoughts:

It has really worried me to see how, in so many managerial minds, ToC has become another rigid linear framework – and another ‘management requirement’. This trivialises the entire conversation around theories of change.

The question should NOT be whether or not you have a theory of change (there is some kind of theory informing any action), but what kind of theory of change you have!

A log frame is a kind of theory of change. It expresses the hypothesis that certain actions will lead to certain outcomes. But log frames usually generate a very rigid theory that is only useful when the entire change process is within the organizations’ sphere of control. When we can be pretty certain that if we do X then Y will come about. That there are no other actors or conditions that can influence our intended outcome. In other words, logframes are a good tool where there is a clear and simple direct causal relationship between the actions and the outcome.

A log frame is a bad framework to apply to more complex change processes that are not completely within an organizations sphere of control – where results can be influenced by many actors and conditions, where there is uncertainty and where sustaining change requires constant reflection, learning and re-adjusting relationships and strategies.

Developing a useful theory of change that can effectively guide strategy and learning in complex change process requires a very different approach. But there are tools that can help.

There is a growing body of good work and experience out there – as Adinda has illustrated. Outcome mapping is another approach that helps clarify a useful theory of change for complex processes. At Keystone Accountability (www.keystoneaccountability.org) we have also developed an approach and set of tools that we think can help here – at least the clients that we have used these with have spoken very positively about this experience. Until they are hit by donor requirements for a logframe and most of the flexibility and creativity is quietly buried.

But the second thing I want to say is just as important. A good theory of change (or hypothesis about what you and those you work with think is needed for change to happen and be sustained) must constantly be tested to see if its predictions are still valid. And it must be revised and adapted where the evidence shows that this is necessary.

This means that a program must constantly be looking for all kinds of evidence of changes that affirm or cause them to question their theory. And one of the best sources of evidence is systematic feedback on the relationships and the perceived changes taking place in the lives of those most affected by the intervention.

At Keystone, we have been developing tools and a methodology for regularly and systematically collecting, analysing and reporting perceptual evidence of the performance of an intervention against the key elements of the intervention’s theory of change. We call this emerging method ‘constituent voice’ and it combines the practical data collection techniques of the customer satisfaction industry in the business world with participatory developmental learning processes.

We think we are beginning to understand what kind of performance data can be collected quickly, cost-effectively and regularly to generate ongoing and incremental evidence of an organization’s developmental impact – planned or unplanned, alone or with or against others. We think we are learning how to collect, analyse and communicate this evidence through words and graphics so that it can form the basis of evidence-based dialogue among all constituents of the change process: funders, implementers and those intended to benefit.

We think that this approach has the potential to become a movement and would love to work with anyone who would like to walk this road with or alongside us.

Very interesting proposition! This is one step further down the road, responding to the question what kind of methods or tools could be useful for collecting relevant and adequate data for measuring performance of interventions against their theory of change. Constituent voice essentially produces perceptional satisfaction data that could become extremely powerful in scaling-up the voice of the poor and forcing responsible development actors to listen to what their “clients” (poor people) think about their development efforts and its effects on their lives and futures. It has the potential of becoming a very powerful AND empowering instrument for collaborative learning and collective accountability to the poor.

I believe though that no single method or tool or framework on its own can make the holy grail and bring about real transformation. Therefore I would LOVE to explore how this method could be combined in a complex systems-thinking approach to impact measurement and learning –from a rights perspective– and so I would say, Andre: can we talk more?

I’d like to support the different view of what purpose a theory of change should serve and how it then should be conceptualized and used with the example of Oxfam America’s long-term rights-based programs.

Oxfam America’s programs incorporate shared impact measurement and learning systems designed to produce evidence of complex systemic change towards achieving collective impact goals over the longer term. Rather than trying to attribute results to a single intervention or a single actor, these systems attempt to build the case for plausible contributions and promote dialogue among key stakeholders and partners about the pattern or dynamics leading to the desired changes. Two elements are critical for this: (a) visualizing the program’s theory of change so that partners and stakeholders can fully capture the envisioned changes presumably leading to the aspired impact goal; and (b) attaching a manageable set of indicators to the theory of change that facilitates collaborative and evidence-based reflection and learning against the theory of change. However, in order for the theory of change to become/remain a useful instrument for reflection and learning together with representatives of different stakeholders with different backgrounds, it needs to be something that is fluent and flexible and somehow captures all the different views and expectations…

In mainstream development practice, a theory of change is often used as the summary of a program’s or project’s intervention logic (mostly identical to the Logical Framework method) that (a) starts from what the leading organization wants to do, (b) identifies the results that may come out of this, and (c) uses evaluation to learn whether the actions are leading to the expected results. Such an approach tends to be unaware of different perspectives, believes and assumptions, and blind to developments outside the intervention logic. Those assumptions that are made explicit and listed in the left column of the LogFrame are to be “managed” but not used as a vehicle for reflection and learning with the stakeholders. Such an approach moreover makes it difficult to discover and explain unpredictable or “non-logical” changes and remain open to viable alternatives for action.

In Oxfam America’s approach, a Theory of Change takes the collective impact goal as its starting point and visualizes a plausible pathway of changes moving backwards from that goal. It does not include or suggest actions or strategies—only the hypothetical changes anticipated at interrelated levels (local, intermediate, national, and regional or international)–, and it makes explicit how partners and stakeholders believe change might happen. It serves as a working hypothesis that is regularly updated when new conditions and trends are emerging in the context.

The Theory of Change doesn’t need to be perfect but good enough to make the complexity of a rights-based program comprehensible for partners and key stakeholders. This implies an emergent modeling through iterative reflection and learning, for helping participants explore plausible hypotheses and understand the changes occurring in certain circumstances. The context, relationships, partner capacities and program levels & conditions are different in every program area and time frame, but the Theory of Change should keep partners and key stakeholders focused on the program’s impact goal and serve as the basis for ongoing dialogue about what constitutes real change in terms of empowerment, and how to arrive at that.

Evidence-based and collaborative learning against the theory of change is facilitated by connecting indicators to key points in the change model. There is no clear-cut, one-to-one relationship between indicators and outcomes, since presumably they can only say something meaningful about systemic change if they are measured as a system. The indicators are composites, depending on variables also influencing other indicators. The variables perceived as relevant for measuring a particular indicator at one point in time may be inadequate or outdated later, as the system’s characteristics are constantly changing. The variables or questions for measuring the indicators have to be determined and regularly reviewed, therefore, in close collaboration with the key stakeholders, through iterative impact research and outcome monitoring.

A theory of change of a program in this way essentially becomes a very dynamic instrument for ongoing reflection and learning with the development actors and for holding each other accountable for taking up their roles and responsibilities.

This sounds really great, indeed, but the trick is that it remains but an “instrument” that cannot be used or applied in the same way everywhere in every context. In certain contexts it might prove to be extremely difficult because it is counter-intuitive to the dominant cultural norms, values and world views and conflicting with the political establishments.

Something I forgot to say:

A theory of change of a program can take different shapes and forms and can have multiple versions depending on the focus and level of attention, the moment in the lifetime of the program, and the stakeholders involved at that moment. Largely it should have an outline visual that remains quite the same during the whole program. But that’s only a “generic” that helps the people involved think through what it actually means from where they are sitting in the system. The farmers in the water program in Ethiopia for instance clearly said that the illustration or visual of the program’s theory of change need a more refined version for each locality where the program is running, reflecting the characteristics specific to these localities, which tend to be quite diverse across Ethiopia.

It’s also fascinating to see how theories of change are drawn and used differently by partners and stakeholders in Central America for instance as compared to East Africa. Perhaps the historical background of the organizations and groups involved are playing out here. In Latin America for instance it’s a more dynamic process with lively debate producing multiple versions of a program’s theory of change, while in East Africa it tends to be much more of a static instrument that guides planning and monitoring and consolidates different views…

I’d love to learn more about the ‘other approach’ you mention to Theories of Change…does it have a name?

I really like this post. It’s particularly timely for Engineers Without Borders Canada as we’ve started to really use the term ‘Theory of Change’. We’re aiming to get at something that’s flexible, appropriate to the context, recognizes assumptions and hypothesis as just what they are – something that may be wrong, we actively test hypothesis and review assumptions.

Any additional thoughts or resources would be appreciated!

Thanks,

Sarah

Co-Director of African Programs, Engineers Without Borders Canada

Hi Sarah,

I am glad you you found it useful. Hmm – not sure how to label the appraoch I am advocating. Perhaps others have some ideas? Another useful resource in addition to Cathy James’ is Inigo Retolaza’s guide A Theory of Change: A thinking and action approach to navigate in the complexity of social change processes. The Dutch NGO, Hivos, with whom Inigo worked on this currently has a D group discussion that you might want to join.

Rosalind

Thank you everyone for your resources and further advice. The resources around facilitating meetings – from Keystone are particularly relevant to us. Cathy James’ and Inigo Retolaza’s guide helped stimulate more thoughtfulness around our own definition of theory of change.