Epistemology: the elephant in the room?

A key take away message for me about the exchange on evidence with Chris Whitty and Stefan Dercon on the From Poverty to Power blog was the challenge of communicating complex ideas simply, cialis particularly, the difficulties of clearly explaining the importance of different ways of looking at the world. In her recent blog Cathy Shutt pointed out some great comments on this, notably the tweet from @ScepSec ‘Not sure what troubles me most. The twitterati’s inability 2 see the message or Roche & Eyben’s ina bility to express it’. Inadequate communication can result in those with different perspectives ‘talking past each other’, as suggested by Duncan Green in his summary of the debate.

bility to express it’. Inadequate communication can result in those with different perspectives ‘talking past each other’, as suggested by Duncan Green in his summary of the debate.

Understanding different perspectives is important not only to get to grips with ‘evidence’ but also to assess how successfully ‘wicked’ problems are being tackled. For example, understanding the issue of violence against women requires inquiring into the perspectives and world-views of those involved – including victims and perpetrators, as well as citizens, legislators, governments and donors. And doing this well requires an understanding of epistemology i.e. what kinds of knowledge are considered valid, as well as methodology i.e. how this knowledge can be generated.

So, despite not being an expert on these matters and at the risk of further confusing everyone (the ‘totally confused’ vote currently stands at 20% of the From Poverty to Power poll on the debate), here are some thoughts on my journey through these issues and words from a monitoring and evaluation angle.

Working at an International NGO, it soon became clear that people have different world views, shaped by culture, gender, identity, religion etc. So far so good.

However, those tedious philosophical questions of the ‘how do we know what we know?’ type, or ‘if a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?’ genre, seemed at best unhelpful, or worse made my head hurt.

However, those tedious philosophical questions of the ‘how do we know what we know?’ type, or ‘if a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?’ genre, seemed at best unhelpful, or worse made my head hurt.

Yet as I got more involved in monitoring and evaluation, questions similar to these – albeit of a more practical nature – kept being asked, i.e. ‘how do we know we are doing a good job?’

At this stage I started trying to reconcile the fact that people have different ways of understanding the world with the need to make some judgements about how our NGO was ‘intervening’ in that world.

It seemed to me there were some obvious principles. First that the views and opinions of those that our NGO was seeking to benefit had to have a central place in the process, as did our ‘front-line’ staff who were closest to them. Second there is a need to cross check these views through other observations, including using the facts, figures and judgements of others – even if this leads to simply understanding that different standpoints are irreconcilable. And third that no matter how good the monitoring and evaluation, if the findings were never used and the lessons generated never learnt, then it was a waste of time and money.

Over time also it also became clearer that power relations and vested interests are central to the process: within the community; amongst evaluators; within the organisation and between all of them and the back donors. In fact, as others have observed, evaluation is inherently a political activity.

This growing understanding of power and its visible, hidden and invisible elements also helped me to understand better how influence is exercised at many levels, including in shaping how problems are defined and addressed. Through our actions those of us in powerful positions are, often inadvertently, reproducing certain ways of looking at the world, e.g. about the role of women in society. Thus Robert Chambers, in this paper, argues that it is difficult to exaggerate the central importance of being self critically aware of our power in this respect.

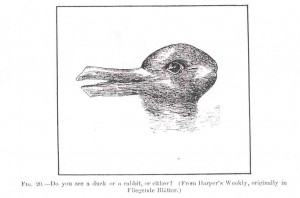

I therefore found it easier to see how dominant ideas or paradigms frame what forms of inquiry are generally deemed valid, what questions should be asked and how they should be answered. It is also no surprise that this leads to ‘paradigm wars’ between competing world views and philosophies, which then play out in areas like monitoring and evaluation. Many of the battles relate to whether knowledge is “discovered” (i.e. by objective experiments), or whether it is “constructed” in a social context (and therefore not value-free or objective). This then leads to questions about whether researchers (or evaluators) can be truly separate from the subject of their inquiry.

Many engaged in the daily practice of development, like an emerging group of evaluators, probably take a pragmatic stance. They feel that academic debates on ‘epistemology’ and paradigms are a slightly bewildering sideshow to how they respond to the combined pressures of wanting to do a better job, whilst at the same time meeting the demands for certain types of evidence.

Yet these debates have much relevance for practitioners, as they need to be aware of the frames within which they, and others, operate. This permits greater self-awareness and reflective practice, and therefore conscious choice. It also allows for a greater understanding of other perspectives, including how power and politics play out in the gathering and use of evidence. The onus is perhaps on the growing number of scholar practitioners or ‘pracademics’ to help make these issues more accessible, and to encourage a richer debate.

Comments are closed.

This certainly resonates with my experience of collaboration within NGOs and the difficulty of trying to work across disciplines in universities! It’s a hard thing to bring to surface and talk about – as often we are unaware of our own epistemological biases and where they come from and they frequently involve us rejecting the assumptions of other approaches which can make other peoples’ views all too easy to dismiss.

This post also made me think about how much epistemological divergences underpin other kinds of debates about development decision-making and participation. For example, in the case of hydropower dam development, a significant amount of the conflict since the 1970s has been between a preference for project decision-making based on technical, economic and financial information, those who demand the incorporation (or prioritisation) of environmental and social knowledge, and, even further, those claiming recognition of radically different epistemologies – for example Indigenous understandings of the environment. The impacts of talking past each other about dams had pretty serious consequences – as documented by the World Commission on Dams report in 2001.